As executive vice president of people and communications at American Airlines, Elise Eberwein’s role within the structure of the organization might not be readily apparent. After all, you might ask, doesn’t corporate communications typically involve marketing? And what does that have to do with organizational structure? As it turns out, quite a bit at the world’s largest airline.

When American Airlines and US Airways finally got the U.S. government’s approval to merge in late 2013, it was no longer business as usual for Eberwein and her colleagues at the “new” airline. Until the merger, which basically produced the world’s largest airline with more than 6,000 daily flights and 102,900 employees, Eberwein was head of communications at US Airways—a position she held for nine years after various other jobs in the airline industry.

Communications and aviation are in Eberwein’s DNA. She worked as a flight attendant at TWA before moving on to manage communications at Denver-based Frontier Airlines. Her next communications experience was at America West, which then merged with US Airways, where Eberwein served as executive vice president of people, communications, and public affairs before she took over the chief communications job at American Airlines.

Corporation communications is no longer just about marketing. The importance of an effective communications strategy cannot be understated in today’s 24/7 business environment. Corporate communication executives have taken on an expanded role in many organizations, according to a recent survey by the Korn Ferry Institute. Of the senior communications executives from Fortune 500 companies who responded to the survey, nearly 40 percent said chief communications officers report directly to the CEO. In addition, more than two-thirds of respondents believe the most important leadership characteristic for communications professionals is having a strategic mindset that goes beyond day-to-day communications activities and looks ahead to future possibilities that can be translated into achievable corporate strategies at all levels of the organization.

In a company as large as American Airlines, even after the initial two-year integration plan, there are many departments, unions, and other employees to communicate with on a daily basis, not to mention the millions of customers they serve every day. For example, American’s social media hub consists of 30 or so team members, divided into three groups: social customer service, social engagement, and social insights. The customer service group, the largest of the three, operates around the clock to address customers’ issues, including missed flight connections and lost luggage, as well as quirky questions like why American airplanes have a specific number of stripes on their tails. Reporting to Eberwein, the social media group is empowered to reach out to any company department directly to get answers for any customer.

Eberwein believes her role includes working closely with the CEO and other managers across the globe to provide consistent, detailed information to all of its stakeholders. To accomplish this feat, Eberwein and other senior managers hold a weekly Monday morning meeting to review the previous week’s operations data, revenue results, and people engagement activities. Eberwein believes establishing this regular contact with colleagues across the organization helps reinforce American’s commitment to engagement and transparent communications, which ultimately shapes the customer’s experience as well as the entire company.

Sources: “Leadership Bios: Elise Eberwein,” https://www.aa.com, accessed July 24, 2017; “By the Numbers: Snapshot of the Airline,” http://news.aa.com, accessed July 24, 2017; Richard Marshall, Beth Fowler, and Nels Olson, “The Chief Communications Officer: Survey and Findings among the Fortune 500,” https://www.kornferry.com, accessed July 24, 2017; Elise Eberwein, “Why the Chief Communications Officer Is Pivotal to the CEO, Especially a New One,” Chief Executive, http://chiefexecutive.net, September 11, 2016; Michael Slattery, “A Visit to American Airlines Social Media Hub,” Airways magazine, https://airwaysmag.com, June 10, 2016; Diana Bradley, “American Airlines CEO Discusses Comms Strategy behind US Airways Merger,” PR Week, http://www.prweek.com, May 27, 2015.

This module focuses on the different types of organizational structure, the reasons an organization might prefer one structure over another, and how the choice of an organizational structure ultimately can impact that organization’s success.

In today’s dynamic business environment, organizational structures need to be designed so that the organization can quickly respond to new competitive threats and changing customer needs. Future success for companies will depend on their ability to be flexible and respond to the needs of customers. In this chapter, we’ll look first at how companies build organizational structures by implementing traditional, contemporary, and team-based models. Then, we’ll explore how managers establish the relationships within the structures they have designed, including determining lines of communication, authority, and power. Finally, we’ll examine what managers need to consider when designing organizational structures and the trends that are changing the choices companies make about organizational design.

The key functions that managers perform include planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. This module focuses specifically on the organizing function. Organizing involves coordinating and allocating a firm’s resources so that the firm can carry out its plans and achieve its goals. This organizing, or structuring, process is accomplished by:

The result of the organizing process is a formal structure within an organization. An organization is the order and design of relationships within a company or firm. It consists of two or more people working together with a common objective and clarity of purpose. Formal organizations also have well-defined lines of authority, channels for information flow, and means of control. Human, material, financial, and information resources are deliberately connected to form the business organization. Some connections are long-lasting, such as the links among people in the finance or marketing department. Others can be changed at almost any time—for example, when a committee is formed to study a problem.

Every organization has some kind of underlying structure. Typically, organizations base their frameworks on traditional, contemporary, or team-based approaches. Traditional structures are more rigid and group employees by function, products, processes, customers, or regions. Contemporary and team-based structures are more flexible and assemble employees to respond quickly to dynamic business environments. Regardless of the structural framework a company chooses to implement, all managers must first consider what kind of work needs to be done within the firm.

The process of dividing work into separate jobs and assigning tasks to workers is called division of labor . In a fast-food restaurant, for example, some employees take or fill orders, others prepare food, a few clean and maintain equipment, and at least one supervises all the others. In an auto assembly plant, some workers install rearview mirrors, while others mount bumpers on bumper brackets. The degree to which the tasks are subdivided into smaller jobs is called specialization . Employees who work at highly specialized jobs, such as assembly-line workers, perform a limited number and variety of tasks. Employees who become specialists at one task, or a small number of tasks, develop greater skill in doing that particular job. This can lead to greater efficiency and consistency in production and other work activities. However, a high degree of specialization can also result in employees who are disinterested or bored due to the lack of variety and challenge.

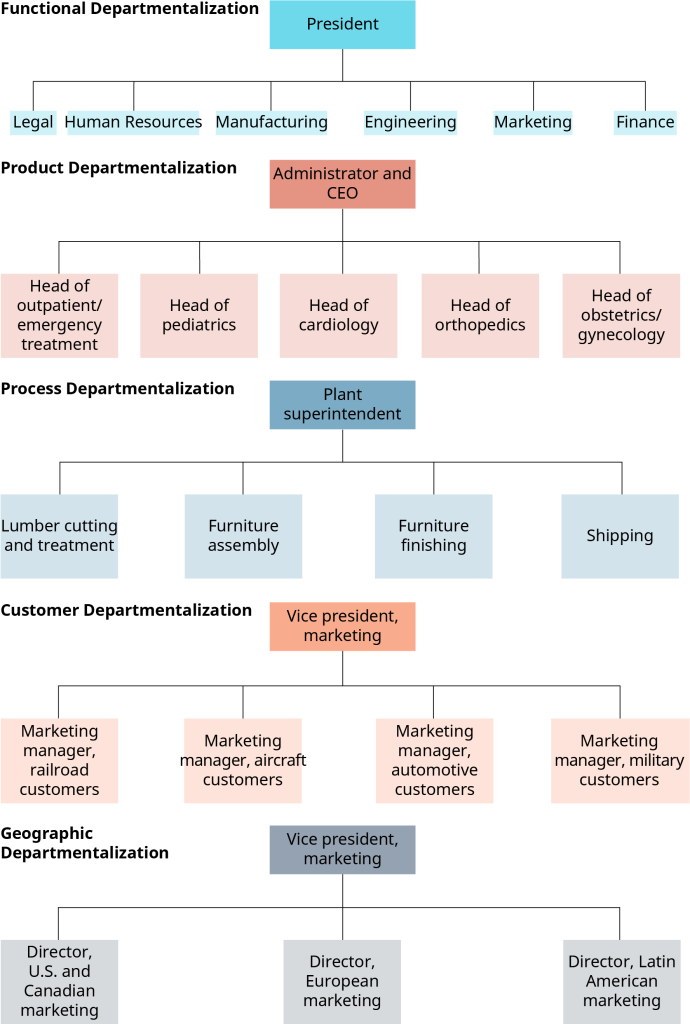

After a company divides the work it needs to do into specific jobs, managers then group the jobs together so that similar or associated tasks and activities can be coordinated. This grouping of people, tasks, and resources into organizational units is called departmentalization . It facilitates the planning, leading, and control processes.

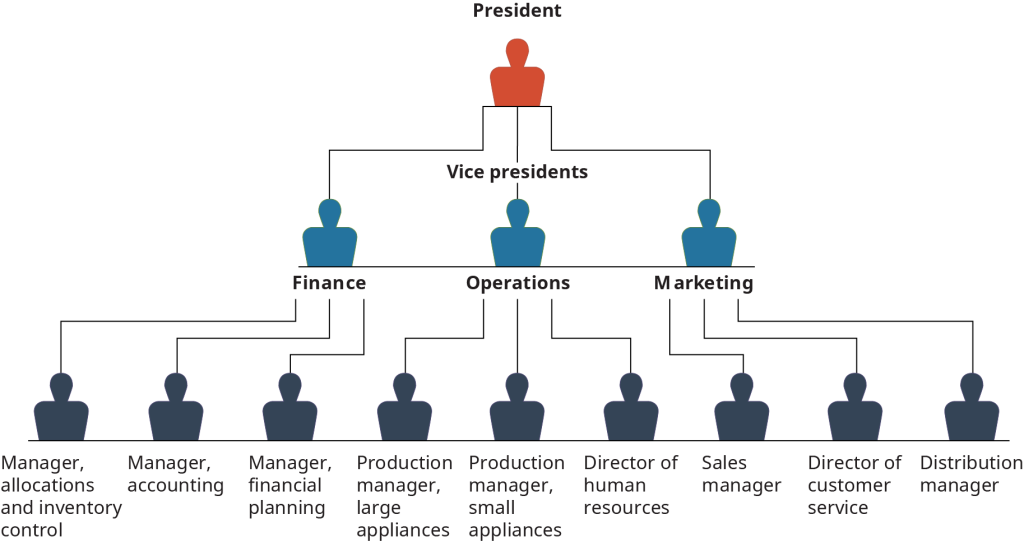

An organization chart is a visual representation of the structured relationships among tasks and the people given the authority to do those tasks. In the organization chart in Exhibit 7.4, each figure represents a job, and each job includes several tasks. The sales manager, for instance, must hire salespeople, establish sales territories, motivate and train the salespeople, and control sales operations. The chart also indicates the general type of work done in each position. As Exhibit 7.5 shows, five basic types of departmentalization are commonly used in organizations:

Making a strategic change to a company’s overall philosophy and the way it does business affects every part of the organizational structure. And when that change pertains to sustainability and “clean food,” Panera Bread Company took on the challenge more than a decade ago and now has a menu free of man-made preservatives, sweeteners, colors, and flavors.

In 2015, Ron Shaich, company founder and CEO, announced Panera’s “no-no” list of nearly 100 ingredients, which he vowed would be eliminated or never used again in menu items. Two years later, the company announced that its menu was “100 percent clean,” but the process was not an easy one.

Panera used thousands of labor hours to review the 450 ingredients used in menu items, eventually reformulating more than 120 of them to eliminate artificial ingredients. Once the team identified the ingredients that were not “clean,” they worked with the company’s 300 vendors—and in some instances, a vendor’s supplier—to reformulate an ingredient to make it preservative-free. For example, the recipe for the company’s popular broccoli cheddar soup had to be revised 60 times to remove artificial ingredients without losing the soup’s taste and texture. According to Shaich, the trial-and-error approach was about finding the right balance of milk, cream, and emulsifiers, like Dijon mustard, to replace sodium phosphate (a no-no item) while keeping the soup’s texture creamy. Panera also created a new cheddar cheese to use in the soup and used a Dijon mustard that contained unpreserved vinegar as a substitute for the banned sodium phosphate.

Sara Burnett, Panera’s director of wellness and food policy, believes that the company’s responsibility goes beyond just serving its customers. She believes that Panera can make a difference by using its voice and purchasing power to have a positive impact on the overall food system. In addition, the company’s Herculean effort to remove artificial ingredients from its menu items also helped it take a close look at its supply chain and other processes that Panera could simplify by using better ingredients.

Panera is not yet satisfied with its commitment to clean food. The food chain recently announced its goal of sourcing 100 percent cage-free eggs for all of its U.S. Panera bakery-cafés by 2020.

Critical Thinking QuestionsSources: “Our Food Policy,” https://www.panerabread.com, accessed July 24, 2017; Emily Payne, “Panera Bread’s Sara Burnett on Shifting Demand for a Better Food System,” Food Tank, http://foodtank.com, accessed July 18, 2017; Julie Jargon, “What Panera Had to Change to Make Its Menu ‘Clean,’” The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com, February 20, 2017; John Kell, “Panera Says Its Food Menu Is Now 100% ‘Clean Eating,’” Fortune, http://fortune.com, January 13, 2017; Lani Furbank, “Seven Questions with Sara Burnett, Director of Wellness and Food Policy at Panera Bread,” Food Tank, https://foodtank.com, April 12, 2016.

The line organization is designed with direct, clear lines of authority and communication flowing from the top managers downward. Managers have direct control over all activities, including administrative duties. An organization chart for this type of structure would show that all positions in the firm are directly connected via an imaginary line extending from the highest position in the organization to the lowest (where production of goods and services takes place). This structure, with its simple design and broad managerial control, is often well-suited to small, entrepreneurial firms.

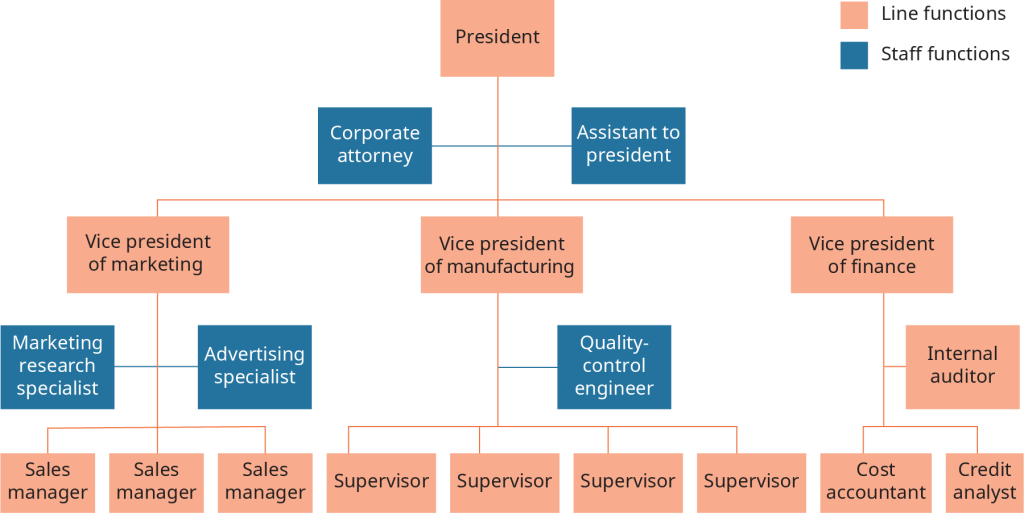

As an organization grows and becomes more complex, the line organization can be enhanced by adding staff positions to the design. Staff positions provide specialized advisory and support services to line managers in the line-and-staff organization , shown in Exhibit 7.6. In daily operations, individuals in line positions are directly involved in the processes used to create goods and services. Individuals in staff positions provide the administrative and support services that line employees need to achieve the firm’s goals. Line positions in organizations are typically in areas such as production, marketing, and finance. Staff positions are found in areas such as legal counseling, managerial consulting, public relations, and human resource management.

Although traditional forms of departmentalization still represent how many companies organize their work, newer, more flexible organizational structures are in use at many firms. Let’s look at matrix and committee structures and how those two types of organizations are helping companies better leverage the diverse skills of their employees.

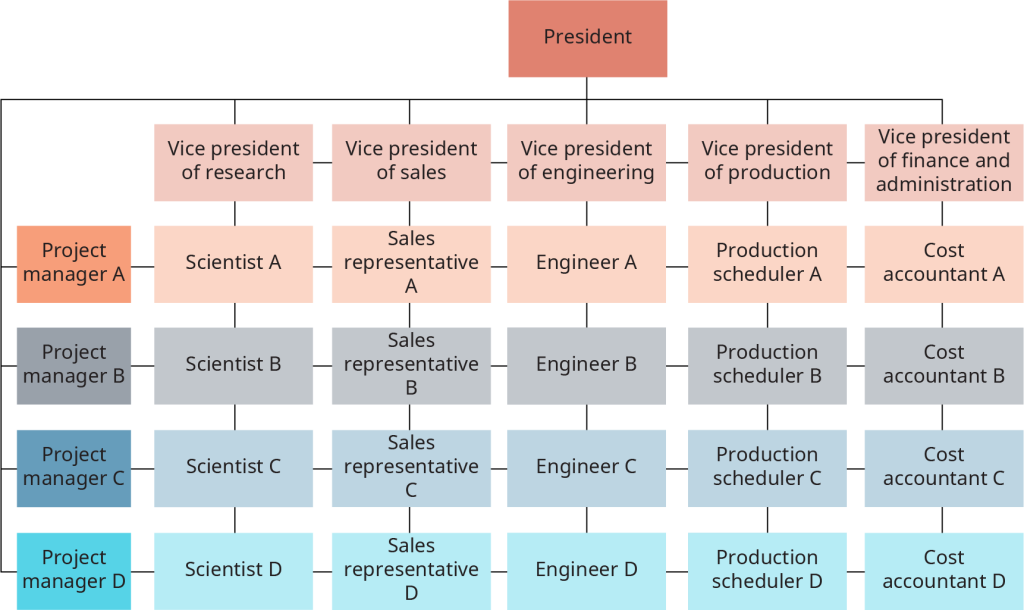

The matrix structure (also called the project management approach) is sometimes used in conjunction with the traditional line-and-staff structure in an organization. Essentially, this structure combines two different forms of departmentalization, functional and product, that have complementary strengths and weaknesses. The matrix structure brings together people from different functional areas of the organization (such as manufacturing, finance, and marketing) to work on a special project. Each employee has two direct supervisors: the line manager from her or his specific functional area and the project manager. Exhibit 7.7 shows a matrix organization with four special project groups (A, B, C, D), each with its own project manager. Because of the dual chain of command, the matrix structure presents some unique challenges for both managers and subordinates.

Advantages of the matrix structure include:

Disadvantages of the matrix structure include:

Although project-based matrix organizations can improve a company’s flexibility and teamwork, some companies are trying to unravel complex matrix structures that create limited accountability and complicate day-to-day operations. Some CEOs and other top managers suggest that matrix structures make it easier to blame others when things don’t go as planned. 7

In committee structure , authority and responsibility are held by a group rather than an individual. Committees are typically part of a larger line-and-staff organization. Often the committee’s role is only advisory, but in some situations the committee has the power to make and implement decisions. Committees can make the coordination of tasks in the organization much easier. For example, Novartis, the huge Swiss pharmaceutical company, has a committee structure, which reports to its board of directors. The company’s executive committee is responsible for overseeing the business operations of group companies within the global organization and consists of the CEO, CFO, head of HR, general counsel, president of operations, head of biomedical research, global head of drug development, CEOs of the pharmaceutical and oncology units, and CEOs of Sandoz and Alcon , other Novartis companies. Members of the executive committee are selected by the company’s board of directors. 8

Committees bring diverse viewpoints to a problem and expand the range of possible solutions, but there are some drawbacks. Committees can be slow to reach a decision and are sometimes dominated by a single individual. It is also more difficult to hold any one individual accountable for a decision made by a group. Committee meetings can sometimes go on for long periods of time with seemingly little being accomplished.

One of the most apparent trends in business today is the use of teams to accomplish organizational goals. Using a team-based structure can increase individual and group motivation and performance. This section gives a brief overview of group behavior, defines work teams as specific types of groups, and provides suggestions for creating high-performing teams.

Teams are a specific type of organizational group. Every organization contains groups, social units of two or more people who share the same goals and cooperate to achieve those goals. Understanding some fundamental concepts related to group behavior and group processes provides a good foundation for understanding concepts about work teams. Groups can be formal or informal in nature. Formal groups are designated and sanctioned by the organization; their behavior is directed toward accomplishing organizational goals. Informal groups are based on social relationships and are not determined or sanctioned by the organization.

Formal organizational groups, like the sales department at Apple , must operate within the larger Apple organizational system. To some degree, elements of the larger Apple system, such as organizational strategy, company policies and procedures, available resources, and the highly motivated employee corporate culture, determine the behavior of smaller groups, such as the sales department, within the company. Other factors that affect the behavior of organizational groups are individual member characteristics (e.g., ability, training, personality), the roles and norms of group members, and the size and cohesiveness of the group. Norms are the implicit behavioral guidelines of the group, or the standards for acceptable and unacceptable behavior. For example, an Apple sales manager may be expected to work at least two Saturdays per month without extra pay. Although this isn’t written anywhere, it is the expected norm.

Group cohesiveness refers to the degree to which group members want to stay in the group and tend to resist outside influences (such as a change in company policies). When group performance norms are high, group cohesiveness will have a positive impact on productivity. Cohesiveness tends to increase when the size of the group is small, individual and group goals are similar, the group has high status in the organization, rewards are group-based rather than individual-based, and the group competes with other groups within the organization. Work group cohesiveness can benefit the organization in several ways, including increased productivity, enhanced worker self-image because of group success, increased company loyalty, reduced employee turnover, and reduced absenteeism. Southwest Airlines is known for its work group cohesiveness. On the other hand, cohesiveness can also lead to restricted output, resistance to change, and conflict with other work groups in the organization.

The opportunity to turn the decision-making process over to a group with diverse skills and abilities is one of the arguments for using work groups (and teams) in organizational settings. For group decision-making to be most effective, however, both managers and group members must understand its strengths and weaknesses (see Table 7.1).

We have already noted that teams are a special type of organizational group, but we also need to differentiate between work groups and work teams. Work groups share resources and coordinate efforts to help members better perform their individual duties and responsibilities. The performance of the group can be evaluated by adding up the contributions of the individual group members. Work teams require not only coordination but also collaboration, the pooling of knowledge, skills, abilities, and resources in a collective effort to attain a common goal. A work team creates synergy, causing the performance of the team as a whole to be greater than the sum of team members’ individual contributions. Simply assigning employees to groups and labeling them a team does not guarantee a positive outcome. Managers and team members must be committed to creating, developing, and maintaining high-performance work teams. Factors that contribute to their success are discussed later in this section.

The evolution of the team concept in organizations can be seen in three basic types of work teams: problem-solving, self-managed, and cross-functional. Problem-solving teams are typically made up of employees from the same department or area of expertise and from the same level of the organizational hierarchy. They meet on a regular basis to share information and discuss ways to improve processes and procedures in specific functional areas. Problem-solving teams generate ideas and alternatives and may recommend a specific course of action, but they typically do not make final decisions, allocate resources, or implement change.

Many organizations that experienced success using problem-solving teams were willing to expand the team concept to allow team members greater responsibility in making decisions, implementing solutions, and monitoring outcomes. These highly autonomous groups are called self-managed work teams . They manage themselves without any formal supervision, taking responsibility for setting goals, planning and scheduling work activities, selecting team members, and evaluating team performance.

Today, approximately 80 percent of Fortune 1000 companies use some sort of self-managed teams. 9 One example is Zappos ’s shift to self-managed work teams in 2013, where the traditional organizational structure and bosses were eliminated, according to a system called holacracy. 10 Another version of self-managing teams can be found at W. L. Gore , the company that invented Gore-Tex fabric and Glide dental floss. The three employees who invented Elixir guitar strings contributed their spare time to the effort and persuaded a handful of colleagues to help them improve the design. After working three years entirely on their own—without asking for any supervisory or top management permission or being subjected to any kind of oversight—the team finally sought the support of the larger company, which they needed to take the strings to market. Today, W. L. Gore ’s Elixir is the number one selling string brand for acoustic guitar players. 11

An adaptation of the team concept is called a cross-functional team . These teams are made up of employees from about the same hierarchical level but different functional areas of the organization. Many task forces, organizational committees, and project teams are cross-functional. Often the team members work together only until they solve a given problem or complete a specific project. Cross-functional teams allow people with various levels and areas of expertise to pool their resources, develop new ideas, solve problems, and coordinate complex projects. Both problem-solving teams and self-managed teams may also be cross-functional teams.

“Teaming” is the term used at GE Aviation manufacturing plants to describe how self-managed groups of employees are working together to make decisions to help them do their work efficiently, maintain quality, and meet critical deadlines in the global aviation supply chain.

This management concept is not new to GE Aviation; its manufacturing plants in Durham, North Carolina, and Bromont, Quebec, Canada, have been using self-managed teams for more than 30 years. This approach to business operations continues to be successful and is now used at most of its 77 manufacturing facilities worldwide.

The goal of teaming is to move decision-making and authority as close to the end-product as possible, which means front-line employees are accountable for meeting performance goals on a daily basis. For example, if there is some sort of delay in the manufacturing process, it is up to the team to figure out how to keep things moving—even if that means skipping breaks or changing their work schedules to overcome obstacles.

At the Bromont plant, workers do not have supervisors who give them direction. Rather, they have coaches who give them specific goals. The typical functions performed by supervisors, such as planning, developing manufacturing processes, and monitoring vacation and overtime, are managed by the teams themselves. In addition, members from each team sit on a joint council with management and HR representatives to make decisions that will affect overall plant operations, such as when to eliminate overtime and who gets promoted or fired.

This hands-on approach helps workers gain confidence and motivation to fix problems directly rather than sending a question up the chain of command and waiting for a directive. In addition, teaming allows the people who do the work on a daily basis to come up with the best ideas to resolve issues and perform various jobs tasks in the most efficient way possible.

For GE Aviation, implementing the teaming approach has been a successful venture, and the company finds the strategy easiest to implement when starting up a new manufacturing facility. The company recently opened several new plants, and the teaming concept has had an interesting effect on the hiring process. A new plant in Welland, Ontario, Canada, opens soon, and the hiring process, which may seem more rigorous than most job hiring experiences, is well under way. With the team concept in mind, job candidates need to demonstrate not only required technical skills but also soft skills—for example, the ability to communicate clearly, accept feedback, and participate in discussions in a respectful manner.

Critical Thinking QuestionsSources: GE Reports Canada, “The Meaning of Teaming: Empowering New Hires at GE’s Welland Brilliant Factory,” https://gereports.ca, July 17, 2017; Sarah Kessler, “GE Has a Version of Self-Management That Is Much Like Zappos’ Holacracy—and It Works,” Quartz, https://qz.com, June 6, 2017; Gareth Phillips, “Look No Managers! Self-Managed Teams,” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com, June 9, 2016; Amy Alexander, “Step by Step: Train Employees to Take Charge,” Investor’s Business Daily, http://www.investors.com, June 18, 2014; Rasheedah Jones, “Teaming at GE Aviation,” Management Innovation eXchange, http://www.managementexchange.com, July 14, 2013.

A great team must possess certain characteristics, so selecting the appropriate employees for the team is vital. Employees who are more willing to work together to accomplish a common goal should be selected, rather than employees who are more interested in their own personal achievement. Team members should also possess a variety of skills. Diverse skills strengthen the overall effectiveness of the team, so teams should consciously recruit members to fill gaps in the collective skill set. To be effective, teams must also have clearly defined goals. Vague or unclear goals will not provide the necessary direction or allow employees to measure their performance against expectations.

Next, high-performing teams need to practice good communication. Team members need to communicate messages and give appropriate feedback that seeks to correct any misunderstandings. Feedback should also be detached; that is, team members should be careful to critique ideas rather than criticize the person who suggests them. Nothing can degrade the effectiveness of a team like personal attacks. Lastly, great teams have great leaders. Skilled team leaders divide work so that tasks are not repeated, help members set and track goals, monitor their team’s performance, communicate openly, and remain flexible to adapt to changing goals or management demands.

Once companies choose a method of departmentalization, they must then establish the relationships within that structure. In other words, the company must decide how many layers of management it needs and who will report to whom. The company must also decide how much control to invest in each of its managers and where in the organization decisions will be made and implemented.

Managerial hierarchy (also called the management pyramid) is defined by the levels of management within an organization. Generally, the management structure has three levels: top, middle, and supervisory management. In a managerial hierarchy, each organizational unit is controlled and supervised by a manager in a higher unit. The person with the most formal authority is at the top of the hierarchy. The higher a manager, the more power they have. Thus, the amount of power decreases as you move down the management pyramid. At the same time, the number of employees increases as you move down the hierarchy.

Not all companies today are using this traditional configuration. One company that has eliminated hierarchy altogether is t he Morning Star Company , the largest tomato processor in the world. Based in Woodland, California, the company employs 600 permanent “colleagues” and an additional 4,000 workers during harvest season. Founder and sole owner Chris Rufer started the company and based its vision on the philosophy of self-management, in which professionals initiate communication and coordination of their activities with colleagues, customers, suppliers, and others and take personal responsibility for helping the company achieve its corporate goals. 12

An organization with a well-defined hierarchy has a clear chain of command , which is the line of authority that extends from one level of the organization to the next, from top to bottom, and makes clear who reports to whom. The chain of command is shown in the organization chart and can be traced from the CEO all the way down to the employees producing goods and services. Under the unity of command principle, everyone reports to and gets instructions from only one boss. Unity of command guarantees that everyone will have a direct supervisor and will not be taking orders from a number of different supervisors. Unity of command and chain of command give everyone in the organization clear directions and help coordinate people doing different jobs.

Matrix organizations automatically violate the unity of command principle because employees report to more than one boss, if only for the duration of a project. For example, Unilever , the consumer-products company that makes Dove soap, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, and Hellmann’s mayonnaise, used to have a matrix structure with one CEO for North America and another for Europe. But employees in divisions that operated in both locations were unsure about which CEO’s decisions took precedence. Today, the company uses a product departmentalization structure. 13 Companies like Unilever tend to abandon matrix structures because of problems associated with unclear or duplicate reporting relationships—in other words, with a lack of unity of command.

Individuals who are part of the chain of command have authority over other persons in the organization. Authority is legitimate power, granted by the organization and acknowledged by employees, that allows an individual to request action and expect compliance. Exercising authority means making decisions and seeing that they are carried out. Most managers delegate, or assign, some degree of authority and responsibility to others below them in the chain of command. The delegation of authority makes the employees accountable to their supervisor. Accountability means responsibility for outcomes. Typically, authority and responsibility move downward through the organization as managers assign activities to, and share decision-making with, their subordinates. Accountability moves upward in the organization as managers in each successively higher level are held accountable for the actions of their subordinates.

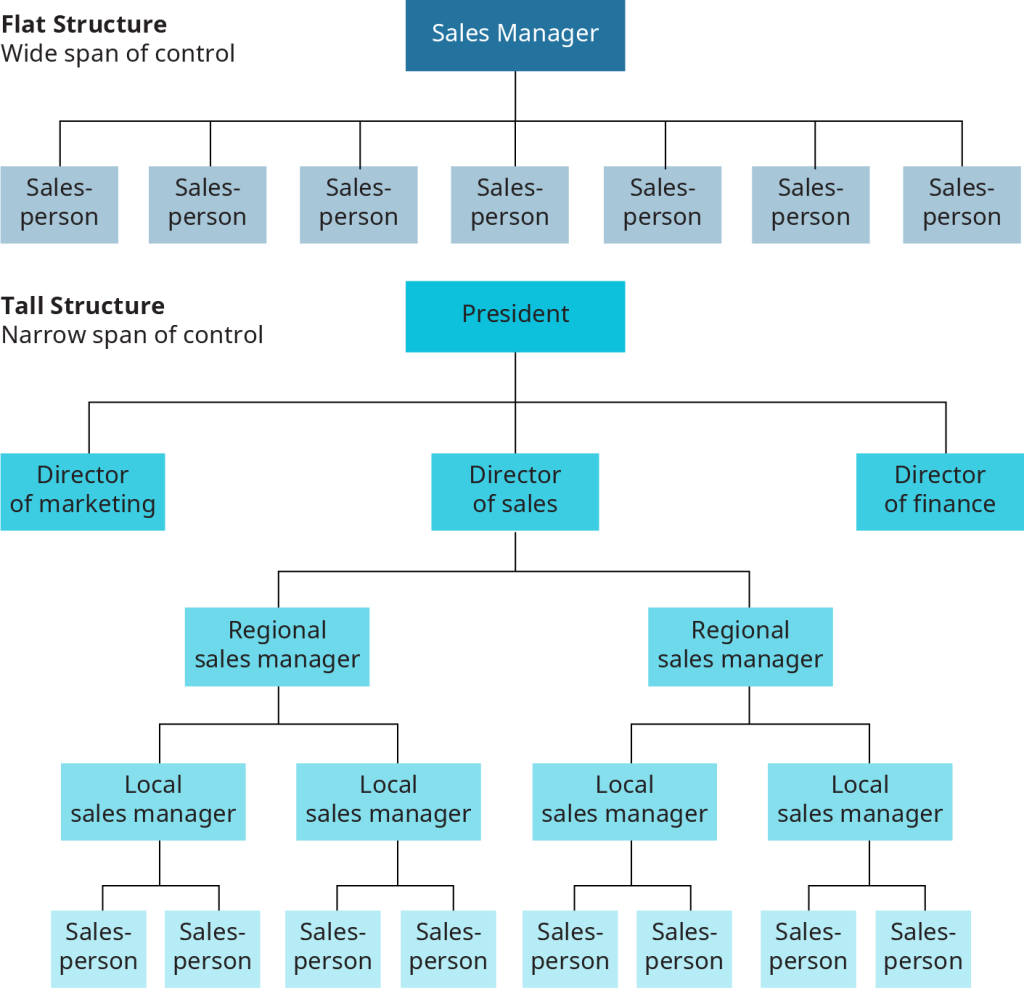

Each firm must decide how many managers are needed at each level of the management hierarchy to effectively supervise the work performed within organizational units. A manager’s span of control (sometimes called span of management) is the number of employees the manager directly supervises. It can be as narrow as two or three employees or as wide as 50 or more. In general, the larger the span of control, the more efficient the organization. As Table 7.2 shows, however, both narrow and wide spans of control have benefits and drawbacks.

If hundreds of employees perform the same job, one supervisor may be able to manage a very large number of employees. Such might be the case at a clothing plant, where hundreds of sewing machine operators work from identical patterns. But if employees perform complex and dissimilar tasks, a manager can effectively supervise only a much smaller number. For instance, a supervisor in the research and development area of a pharmaceutical company might oversee just a few research chemists due to the highly complex nature of their jobs.

How can the degree of centralization/decentralization be altered to make an organization more successful?

The optimal span of control is determined by the following five factors:

The final component in building an effective organizational structure is deciding at what level in the organization decisions should be made. Centralization is the degree to which formal authority is concentrated in one area or level of the organization. In a highly centralized structure, top management makes most of the key decisions in the organization, with very little input from lower-level employees. Centralization lets top managers develop a broad view of operations and exercise tight financial controls. It can also help to reduce costs by eliminating redundancy in the organization. But centralization may also mean that lower-level personnel don’t get a chance to develop their decision-making and leadership skills and that the organization is less able to respond quickly to customer demands.

Decentralization is the process of pushing decision-making authority down the organizational hierarchy, giving lower-level personnel more responsibility and power to make and implement decisions. Benefits of decentralization can include quicker decision-making, increased levels of innovation and creativity, greater organizational flexibility, faster development of lower-level managers, and increased levels of job satisfaction and employee commitment. But decentralization can also be risky. If lower-level personnel don’t have the necessary skills and training to perform effectively, they may make costly mistakes. Additionally, decentralization may increase the likelihood of inefficient lines of communication, competing objectives, and duplication of effort.

Several factors must be considered when deciding how much decision-making authority to delegate throughout the organization. These factors include the size of the organization, the speed of change in its environment, managers’ willingness to give up authority, employees’ willingness to accept more authority, and the organization’s geographic dispersion.

Decentralization is usually desirable when the following conditions are met:

As organizations grow and change, they continually reevaluate their structure to determine whether it is helping the company to achieve its goals.

You are now familiar with the different ways to structure an organization, but as a manager, how do you decide which design will work the best for your business? What works for one company may not work for another. In this section, we’ll look at two generic models of organizational design and briefly examine a set of contingency factors that favors each.

Structural design generally follows one of the two basic models described in Table 7.3: mechanistic or organic. A mechanistic organization is characterized by a relatively high degree of job specialization, rigid departmentalization, many layers of management (particularly middle management), narrow spans of control, centralized decision-making, and a long chain of command. This combination of elements results in what is called a tall organizational structure. The U.S. Army and the United Nations are typical mechanistic organizations.

In contrast, an organic organization is characterized by a relatively low degree of job specialization, loose departmentalization, few levels of management, wide spans of control, decentralized decision-making, and a short chain of command. This combination of elements results in what is called a flat organizational structure. Colleges and universities tend to have flat organizational structures, with only two or three levels of administration between the faculty and the president. Exhibit 7.9 shows examples of flat and tall organizational structures.

Although few organizations are purely mechanistic or purely organic, most organizations tend more toward one type or the other. The decision to create a more mechanistic or a more organic structural design is based on factors such as the firm’s overall strategy, the size of the organization, and the stability of its external environment, among others.

A company’s organizational structure should enable it to achieve its goals, and because setting corporate goals is part of a firm’s overall strategy-making process, it follows that a company’s structure depends on its strategy. That alignment can be challenging for struggling companies trying to accomplish multiple goals. For example, a company with an innovation strategy will need the flexibility and fluid movement of information that an organic organization provides. But a company using a cost-control strategy will require the efficiency and tight control of a mechanistic organization. Often, struggling companies try to simultaneously increase innovation and rein in costs, which can be organizational challenges for managers. Such is the case at Microsoft , where CEO Satya Nadella cut more than 18,000 jobs in 2014 after taking the helm at the technology giant. Most of the cuts were the result of the company’s failed acquisition of Nokia ’s mobile phone business. More recently, the company eliminated additional jobs in sales and marketing (mostly overseas) as Microsoft shifts from a software developer to a cloud computing software delivery service. At the same time, Nadella is also trying to encourage employees and managers to break down barriers between divisions and increase the pace of innovation across the organization. 14

| Mechanistic versus Organic Structure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Structural Characteristic | Mechanistic | Organic |

| Job specialization | High | Low |

| Departmentalization | Rigid | Loose |

| Managerial hierarchy (levels of management) | Tall (many levels) | Flat (few levels) |

| Span of control | Narrow | Wide |

| Decision-making authority | Centralized | Decentralization |

| Chain of command | Long | Short |

Size is another factor that affects how mechanistic or organic a company’s organizational structure is. Much research has been conducted that shows a company’s size has a significant impact on its organizational structure. Smaller companies tend to follow the more organic model, in part because they can. It’s much easier to be successful with decentralized decision-making, for example, if you have only 50 employees. A company with that few employees is also more likely, by virtue of its size, to have a lesser degree of employee specialization. That’s because, when there are fewer people to do the work, those people tend to know more about the entire process. As a company grows, it becomes more mechanistic, as systems are put in place to manage the greater number of employees. Procedures, rules, and regulations replace flexibility, innovation, and independence. That isn’t always the case, however. W. L. Gore has nearly 10,000 employees and more than $3 billion in annual revenues but, as noted earlier, uses an extremely organic organizational structure. Employees have no bosses, participate on teams, and often create roles for themselves to fill functional gaps within the company. 15

Lastly, the business in which a company operates has a significant impact on its organizational structure. In complex, dynamic, and unstable environments, companies need to organize for flexibility and agility. That is, their organizational structures need to respond to rapid and unexpected changes in the business environment. For companies operating in stable environments, however, the demands for flexibility and agility are not so great. The environment is predictable. In a simple, stable environment, therefore, companies benefit from the efficiencies created by a mechanistic organizational structure.

A little less than 20 years ago, Larry Page and Sergey Brin built a search engine that used links to determine the importance of individual pages on the web. Today, Google has grown from two founders to more than 60,000 employees in 50 different countries. While the company is routinely high on the lists of best places to work and companies with the best employee perks, its meteoric growth has not been without challenges.

Much has been written about Google’s informal organizational structure, which has fueled a creative environment second to none. At one point, the founders shared an office that looked like a college dorm room, complete with skateboards, beanbag chairs, and remote-controlled airplanes. The company’s offices around the world are designed to be the most productive workspaces imaginable, sometimes with meeting rooms designed as camping vans (Amsterdam) or hallways decorated with subway grates and fire hydrants (New York City).

As this creative environment expanded, Google relied on its innovative and competitive culture to produce some of the most-used products around the world, including YouTube, the Android operating system, Gmail, and of course, Google Search. As Google grew, so did the strain on its informal structure. In the early days, while adding employees on a daily basis, the company needed to find the right balance between maintaining creativity and running a rapidly growing organization.

In 2001, Brin and Page hired an outside CEO, Eric Schmidt, who hired an HR manager and then divided employees into teams based on product or function. This structure seemed to work well until Google started to acquire companies or develop new products to add to its portfolio of business ventures, including Double Click and Nest. At the same time, Page and Brin never lost sight of their “moonshot” projects, potentially game-changing innovations that could change the world, such as a self-driving car, which may or may not become a profitable venture.

Fast-forward to 2015, when the founders decided Google was getting too big to contain in one company. They created Alphabet, which is now a holding company that includes Google as well as several other business ventures. Their decision to refocus Google and pull out other activities under the Alphabet umbrella has provided transparency and an organizational structure that has been simplified. Sundar Pichai, who was quite successful managing Google Search, became the new Google CEO, while Page became the Alphabet CEO and Brin the Alphabet President. (Former Google CEO Schmidt is Alphabet’s executive chairman.)

This reorganization allows both Brin and Page to focus on projects they are passionate about, such as Project Loon, a network of balloons flying high above commercial airspace that provides web connectivity to remote areas, while leaving Google and its many successful endeavors to be managed independently by Pichai and his team. Alphabet’s recent CFO hire, Ruth Porat, former CFO at Morgan Stanley, has received praise for her guidance in helping company executives take a closer look at costs while still encouraging the innovation and creativity the Google founders seemingly invented. Although not as simple as A–B–C, the new organizational structure seems to streamline processes while allowing the various businesses room to grow on their own.

Critical Thinking QuestionsSources: “Our History,” https://www.google.com, accessed July 24, 2017; “Project Loon: Balloon-Powered Internet for Everyone,” https://x.company, accessed July 24, 2017; Catherine Clifford, “Google Billionaire Eric Schmidt: These 2 Qualities Are the Best Predictors of Success,” CNBC, http://www.cnbc.com, June 26, 2017; Dave Smith, “Read Larry Page’s New Letter about the Current Status of Alphabet, Google’s Parent Company,” Business Insider, http://www.businessinsider.com, April 27, 2017; Avery Hartmans, “Here Are All the Companies and Divisions within Alphabet, Google’s Parent Company,” Business Insider, http://www.businessinsider.com, October 6, 2016; Leena Rao, “CFO Ruth Porat Is Pushing Google ‘Creatives’ to Bring Their Costs under Control,” Fortune, http://fortune.com, September 12, 2016; Adam Lashinsky, “How Alphabet’s Structure Shows Off Google’s True Value,” Fortune, http://fortune.com, February 2, 2016; Carey Dunne, “8 of Google’s Craziest Offices,” Fast Company Design, https://www.fastcodesign.com, April 10, 2014.

Up to this point, we have focused on formal organizational structures that can be seen in the boxes and lines of the organization chart. Yet many important relationships within an organization do not show up on an organization chart. Nevertheless, these relationships can affect the decisions and performance of employees at all levels of the organization.

The network of connections and channels of communication based on the informal relationships of individuals inside the organization is known as the informal organization . Informal relationships can be between people at the same hierarchical level or between people at different levels and in different departments. Some connections are work-related, such as those formed among people who carpool or ride the same train to work. Others are based on nonwork commonalties such as belonging to the same church or health club or having children who attend the same school.

The informal organization has several important functions. First, it provides a source of friendships and social contact for organization members. Second, the interpersonal relationships and informal groups help employees feel better-informed about and connected with what is going on in their firm, thus giving them some sense of control over their work environment. Third, the informal organization can provide status and recognition that the formal organization cannot or will not provide employees. Fourth, the network of relationships can aid the socialization of new employees by informally passing along rules, responsibilities, basic objectives, and job expectations. Finally, the organizational grapevine helps employees to be more aware of what is happening in their workplace by transmitting information quickly and conveying it to places that the formal system does not reach.

The informal channels of communication used by the informal organization are often referred to as the grapevine or the rumor mill. Managers need to pay attention to the grapevines in their organization, because their employees increasingly put a great deal of stock in the information that travels along it, especially in this era of social media. A recent survey found that many business leaders have their work cut out for them in the speeches and presentations they give employees. Survey participants were asked if they would believe a message delivered in a speech by a company leader or one that they heard over the grapevine. Forty-seven percent of those responding said they would put more credibility in the grapevine. Only 42 percent said they would believe senior leadership, and another 11 percent indicated they would believe a blend of elements from both messages. Perhaps even more interesting is how accurate employees perceive their company grapevine to be: 57 percent gave it favorable ratings. “The grapevine may not be wholly accurate, but it is a very reliable indicator that something is going on,” said one survey respondent. 16

With this in mind, managers need to learn to use the existing informal organization as a tool that can potentially benefit the formal organization . An excellent way of putting the informal organization to work for the good of the company is to bring informal leaders into the decision-making process. That way, at least the people who use and nurture the grapevine will have more accurate information to send it.

To improve organizational performance and achieve long-term objectives, some organizations seek to reengineer their business processes or adopt new technologies that open up a variety of organizational design options, such as virtual corporations and virtual teams. Other trends that have strong footholds in today’s organizations include outsourcing and managing global businesses.

Periodically, all businesses must reevaluate the way they do business. This includes assessing the effectiveness of the organizational structure. To meet the formidable challenges of the future, companies are increasingly turning to reengineering —the complete redesign of business structures and processes in order to improve operations. An even simpler definition of reengineering is “starting over.” In effect, top management asks, “If we were a new company, how would we run this place?” The purpose of reengineering is to identify and abandon the outdated rules and fundamental assumptions that guide current business operations. Every company has many formal and informal rules, based on assumptions about technology, people, and organizational goals, that no longer hold. Thus, the goal of reengineering is to redesign business processes to achieve improvements in cost control, product quality, customer service, and speed. The reengineering process should result in a more efficient and effective organizational structure that is better suited to the current (and future) competitive climate of the industry.

One of the biggest challenges for companies today is adapting to the technological changes that are affecting all industries. Organizations are struggling to find new organizational structures that will help them transform information technology into a competitive advantage. One alternative that is becoming increasingly prevalent is the virtual corporation , which is a network of independent companies (suppliers, customers, even competitors) linked by information technology to share skills, costs, and access to one another’s markets. This network structure allows companies to come together quickly to exploit rapidly changing opportunities. The key attributes of a virtual corporation are:

In the concept’s purest form, each company that links up with others to create a virtual corporation is stripped to its essence. Ideally, the virtual corporation has neither a central office nor an organization chart, no hierarchy, and no vertical integration. It contributes to an alliance only its core competencies, or key capabilities. It mixes and matches what it does best with the core competencies of other companies and entrepreneurs. For example, a manufacturer would only manufacture, while relying on a product design firm to decide what to make and a marketing company to sell the end result.

Although firms that are purely virtual organizations are still relatively scarce, many companies are embracing several characteristics of the virtual structure. One example is Cisco Systems . Cisco uses many manufacturing plants to produce its products, but the company owns none of them. In fact, Cisco now relies on contract manufacturers for all of its manufacturing needs. Human hands probably touch fewer than 10 percent of all customer orders, with fewer than half of all orders processed by a Cisco employee. To the average customer, the interdependency of Cisco’s suppliers and inventory systems makes it look like one huge, seamless company.

Technology is also enabling corporations to create virtual work teams. Geography is no longer a limitation when employees are considered for a work team. Virtual teams mean reduced travel time and costs, reduced relocation expenses, and utilization of specialized talent regardless of an employee’s location.

When managers need to staff a project, all they need to do is make a list of required skills and a general list of employees who possess those skills. When the pool of employees is known, the manager simply chooses the best mix of people and creates the virtual team. Special challenges of virtual teams include keeping team members focused, motivated, and communicating positively despite their locations. If feasible, at least one face-to-face meeting during the early stages of team formation will help with these potential problems.

Another organizational trend that continues to influence today’s managers is outsourcing. For decades, companies have outsourced various functions. For example, payroll functions such as recording hours, managing benefits and wage rates, and issuing paychecks have been handled for years by third-party providers. Today, however, outsourcing includes a much wider array of business functions: customer service, production, engineering, information technology, sales and marketing, and more.

Historically, companies have outsourced for two main reasons: cost reduction and labor needs. Often, to satisfy both requirements, companies outsource work to firms in foreign countries. In 2017, outsourcing remains a key component of many businesses’ operations but is not strictly limited to low-level jobs. Some of the insights highlighted in Deloitte ’s recent Global Outsourcing Survey bear this out. According to survey respondents from 280 global organizations, outsourcing continues to be successful because it is adapting to changing business environments. According to the survey, outsourcing continues to grow across mature functions such as HR and IT, but it has successfully moved to nontraditional business functions such as facilities management, purchasing, and real estate. In addition, some businesses view outsourcing as a way of infusing their operations with innovation and using it to maintain a competitive advantage—not just as a way to cut costs. As companies increasingly view outsourcing as more than a cost-cutting strategy, they will be expecting more of their vendors in terms of supplying innovation and other benefits. 17

Another form of outsourcing has become prevalent over the last several years, in part as the result of the slow economic recovery from the global recession of 2007–2009. As many U.S. businesses hesitated to hire full-time workers even as they began to experience gradual growth, some companies began to offer contract work to freelancers, who were not considered full-time employees eligible for company benefits. Known as the gig economy, this work approach has advantages and disadvantages. Some gig workers like the independence of being self-employed, while others acknowledge that they are taking on multiple small projects because they can’t find full-time work as company employees. Another group of individuals work as full-time employees but may sign up for gigs such as driving for Uber or Lyft to supplement their income. Recent estimates suggest that the gig economy may impact more than one-third of the U.S. workforce over the next few years. 18

Despite the challenges, outsourcing programs can be effective. To be successful in outsourcing efforts, managers must do the following:

Recent mergers creating mega-firms (such as Microsoft and LinkedIn , Amazon and Whole Food s, and Verizon and Yahoo ) raise some important questions regarding corporate structure. How can managers hope to organize the global pieces of these huge, complex new firms into a cohesive, successful whole? Should decision-making be centralized or decentralized? Should the firm be organized around geographic markets or product lines? And how can managers consolidate distinctly different corporate cultures? These issues and many more must be resolved if mergers of global companies are to succeed.

Beyond designing a new organizational structure, one of the most difficult challenges when merging two large companies is uniting the cultures and creating a single business. The merger between Pfizer and Pharmacia , makers of Dramamine and Rogaine, is no exception. Failure to effectively merge cultures can have serious effects on organizational efficiency.

As part of its strategic plan for the giant merger, Pfizer put together 14 groups that would make recommendations concerning finances, human resources, operation support, capital improvements, warehousing, logistics, quality control, and information technology. An outside consultant was hired to facilitate the process. One of the first tasks for the groups was to deal with the conqueror ( Pfizer ) versus conquered ( Pharmacia ) attitudes. Company executives wanted to make sure all employees knew that their ideas were valuable and that senior management was listening.

As more and more global mergers take place, sometimes between the most unlikely suitors, companies must ensure that the integration plan includes strategies for dealing with cultural differences, establishing a logical leadership structure, implementing a strong two-way communications channel at all levels of the organization, and redefining the “new” organization’s vision, mission, values, and culture. 20

authority Legitimate power, granted by the organization and acknowledged by employees, that allows an individual to request action and expect compliance. centralization The degree to which formal authority is concentrated in one area or level of an organization. Top management makes most of the decisions. chain of command The line of authority that extends from one level of an organization’s hierarchy to the next, from top to bottom, and makes clear who reports to whom. committee structure An organizational structure in which authority and responsibility are held by a group rather than an individual. cross-functional team Members from the same organizational level but from different functional areas. customer departmentalization Departmentalization that is based on the primary type of customer served by the organizational unit. decentralization The process of pushing decision-making authority down the organizational hierarchy. delegation of authority The assignment of some degree of authority and responsibility to persons lower in the chain of command. departmentalization The process of grouping jobs together so that similar or associated tasks and activities can be coordinated. division of labor The process of dividing work into separate jobs and assigning tasks to workers. formal organization The order and design of relationships within a firm; consists of two or more people working together with a common objective and clarity of purpose. functional departmentalization Departmentalization that is based on the primary functions performed within an organizational unit. geographic departmentalization Departmentalization that is based on the geographic segmentation of the organizational units. group cohesiveness The degree to which group members want to stay in the group and tend to resist outside influences. informal organization The network of connections and channels of communication based on the informal relationships of individuals inside an organization. line organization An organizational structure with direct, clear lines of authority and communication flowing from the top managers downward. line positions All positions in the organization directly concerned with producing goods and services and that are directly connected from top to bottom. line-and-staff organization An organizational structure that includes both line and staff positions. managerial hierarchy The levels of management within an organization; typically includes top, middle, and supervisory management. matrix structure (project management) An organizational structure that combines functional and product departmentalization by bringing together people from different functional areas of the organization to work on a special project. mechanistic organization An organizational structure that is characterized by a relatively high degree of job specialization, rigid departmentalization, many layers of management, narrow spans of control, centralized decision-making, and a long chain of command. organic organization An organizational structure that is characterized by a relatively low degree of job specialization, loose departmentalization, few levels of management, wide spans of control, decentralized decision-making, and a short chain of command. organization The order and design of relationships within a firm; consists of two or more people working together with a common objective and clarity of purpose. organization chart A visual representation of the structured relationships among tasks and the people given the authority to do those tasks. problem-solving teams Usually members of the same department who meet regularly to suggest ways to improve operations and solve specific problems. process departmentalization Departmentalization that is based on the production process used by the organizational unit. product departmentalization Departmentalization that is based on the goods or services produced or sold by the organizational unit. reengineering The complete redesign of business structures and processes in order to improve operations. self-managed work teams Teams without formal supervision that plan, select alternatives, and evaluate their own performance. span of control The number of employees a manager directly supervises; also called span of management. specialization The degree to which tasks are subdivided into smaller jobs. staff positions Positions in an organization held by individuals who provide the administrative and support services that line employees need to achieve the firm’s goals. virtual corporation A network of independent companies linked by information technology to share skills, costs, and access to one another’s markets; allows the companies to come together quickly to exploit rapidly changing opportunities. work groups The groups that share resources and coordinate efforts to help members better perform their individual jobs. work teams Like a work group but also requires the pooling of knowledge, skills, abilities, and resources to achieve a common goal.

Firms typically use traditional, contemporary, or team-based approaches when designing their organizational structure. In the traditional approach, companies first divide the work into separate jobs and tasks. Managers then group related jobs and tasks together into departments. Five basic types of departmentalization are commonly used in organizations:

In recent decades, companies have begun to expand beyond traditional departmentalization methods and use matrix, committee, and team-based structures. Matrix structures combine two types of traditional organizational structures (for example, geographic and functional). Matrix structures bring together people from different functional areas of the organization to work on a special project. As such, matrix organizations are more flexible, but because employees report to two direct supervisors, managing matrix structures can be extremely challenging. Committee structures give authority and responsibility to a group rather than to an individual. Committees are part of a line-and-staff organization and often fulfill only an advisory role. Team-based structures also involve assigning authority and responsibility to groups rather than individuals, but, different from committees, team-based structures give these groups autonomy to carry out their work.

Work groups share resources and coordinate efforts to help members better perform their individual duties and responsibilities. The performance of the group can be evaluated by adding up the contributions of the individual group members. Work teams require not only coordination but also collaboration, the pooling of knowledge, skills, abilities, and resources in a collective effort to attain a common goal. Four types of work teams are used: problem solving, self-managed, cross-functional, and virtual teams. Companies are using teams to improve individual and group motivation and performance.

The managerial hierarchy (or the management pyramid) comprises the levels of management within the organization, and the managerial span of control is the number of employees the manager directly supervises. In daily operations, individuals in line positions are directly involved in the processes used to create goods and services. Individuals in staff positions provide the administrative and support services that line employees need to achieve the firm’s goals. Line positions in organizations are typically in areas such as production, marketing, and finance. Staff positions are found in areas such as legal counseling, managerial consulting, public relations, and human resource management.

In a highly centralized structure, top management makes most of the key decisions in the organization, with very little input from lower-level employees. Centralization lets top managers develop a broad view of operations and exercise tight financial controls. In a highly decentralized organization, decision-making authority is pushed down the organizational hierarchy, giving lower-level personnel more responsibility and power to make and implement decisions. Decentralization can result in faster decision-making and increased innovation and responsiveness to customer preferences.

A mechanistic organization is characterized by a relatively high degree of work specialization, rigid departmentalization, many layers of management (particularly middle management), narrow spans of control, centralized decision-making, and a long chain of command. This combination of elements results in a tall organizational structure. In contrast, an organic organization is characterized by a relatively low degree of work specialization, loose departmentalization, few levels of management, wide spans of control, decentralized decision-making, and a short chain of command. This combination of elements results in a flat organizational structure.

The informal organization is the network of connections and channels of communication based on the informal relationships of individuals inside the organization. Informal relationships can be between people at the same hierarchical level or between people at different levels and in different departments. Informal organizations give employees more control over their work environment by delivering a continuous stream of company information throughout the organization, thereby helping employees stay informed.

Reengineering is a complete redesign of business structures and processes in order to improve operations. The goal of reengineering is to redesign business processes to achieve improvements in cost control, product quality, customer service, and speed.

The virtual corporation is a network of independent companies (suppliers, customers, even competitors) linked by information technology to share skills, costs, and access to one another’s markets. This network structure allows companies to come together quickly to exploit rapidly changing opportunities.

Many companies are now using technology to create virtual teams. Team members may be down the hall or across the ocean. Virtual teams mean that travel time and expenses are eliminated and the best people can be placed on the team regardless of where they live. Sometimes, however, it may be difficult to keep virtual team members focused and motivated.

Outsourcing business functions—both globally and domestically—continues to be a regular business practice for companies large and small. Companies choose to outsource either as a cost-saving measure or as a way to gain access to needed human resource talent and innovation. To be successful, outsourcing must solve a clearly articulated business problem. In addition, managers must use outsourcing providers that fit their company’s actual needs and strive to engage these providers as strategic partners for the long term. A recent phenomenon known as the gig economy has taken on more importance as it pertains to the U.S. labor force and outsourcing. More people are working as freelancers on a per-project basis, either because they can’t get hired as full-time employees or because they prefer to work as self-employed individuals.

Global mergers raise important issues in organizational structure and culture. The ultimate challenge for management is to take two organizations and create a single, successful, cohesive organization.

Recently, the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) announced it would lay off more than 80 IT workers and outsource their jobs to India. This change is part of a larger plan by UCSF to increase its technology outsourcing, which over time could save the organization more than $30 million. A large part of UCSF’s IT work focuses on its hospital services, and many other health care facilities have already outsourced these types of “back-end” jobs to foreign countries.

Working through a multinational contractor that will manage the outsourcing process, UCSF has also asked workers who will soon be out of a job to train their overseas replacements via videoconferencing calls to India. One such worker remarked, “I’m speechless. How can they do this to us?”

A UCSF spokesperson explained that the organization provides millions of dollars in charity care for the poor, and that to continue providing those services, the school has to focus on more specialized tech work related to patients and medical research and send other IT work overseas.

UCSF is not alone in sending IT jobs overseas and making the laid-off workers train their Indian replacements. Recently, ManpowerGroup, a staffing and workforce services firm with more than 3,000 offices worldwide, issued pink slips to 150 workers in Milwaukee whose jobs were outsourced to India.

Using a web search tool, locate articles about this topic and then write responses to the following questions. Be sure to support your arguments and cite your sources.

Ethical Dilemma: Are UCSF and other companies justified in outsourcing technology jobs to India? Do they have any obligation to find other jobs or provide training for displaced workers? Should organizations ask employees who are being laid off to train their replacements?

Sources: Sam Harnett, “Outsourced: In a Twist, Some San Francisco IT Jobs Are Moving to India,” All Tech Considered, http://www.npr.org, accessed July 19, 2017; Dan Shafer, “Exclusive: ManpowerGroup HQ Workers Being Laid Off Required to Train Overseas Replacements,” Milwaukee Business Journal, https://www.bizjournals.com, March 30, 2017; Bill Whitaker, “Are U.S. Jobs Vulnerable to Workers with H-1B Visas?” 60 Minutes, http://www.cbsnews.com, March 19, 2017; Louis Hansen, “After Pink Slips, USCF Tech Workers Train Their Foreign Replacements,” The Mercury News, http://www.mercurynews.com, November 3, 2016.

Imagine an organization with more than 10,000 employees working in 30 countries around the world—with no hierarchy structure. W. L. Gore & Associates, headquartered in Newark, Delaware, is a model of unusual business practices. Wilbert Gore, who left Dupont to explore new uses for Teflon, started the company in 1958. Best known for its breathable, weatherproof Gore-Tex fabric, Glide dental floss, and Elixir guitar strings, the company has no bosses, no titles, no departments, and no formal job descriptions. There is no managerial hierarchy at Gore, and top management treats employees, called associates, as peers.

In 2005, the company named 22-year associate Terri Kelly as its new chief executive officer. Unlike large public corporations, Gore’s announcement was made without much fanfare. Today, more than 12 years later, Kelly continues as chief executive but is the first to admit that it’s not about the CEO at Gore—it’s about the people who work there and their relationships with one another.

The company focuses on its products and company values rather than on individuals. Committees, comprised of employees, make major decisions such as hiring, firing, and compensation. They even set top executives’ compensation. Employees work on teams, which are switched around every few years. In fact, all employees are expected to make minor decisions instead of relying on the “boss” to make them. “We’re committed to how we get things done,” Kelly says. “That puts a tremendous burden on leaders because it’s easier to say ‘Just do it’ than to explain the rationale. But in the long run, you’ll get much better results because people are making a commitment.”

Because no formal lines of authority exist, employees can speak to anyone in the company at any time. This arrangement also forces employees to spend considerable time developing relationships. As one employee described it, instead of trying to please just one “boss,” you have to please everyone. Several years ago the company underwent a “strategy refresh,” conducting surveys and discussions with employees about how they fit into the organization’s culture. Not surprisingly, there was a cultural divide based on multiple generations of workers and length of service stature, which Kelly and her associates have worked hard to overcome. She realizes that not everyone will become a “lifer” at Gore, but recognizes the importance of younger employees who have helped the company become more tech-savvy in communications and stay well-connected in a fast-moving business world.

The informal organizational structure continues to work well. With revenues of $3 billion, the company produces thousands of advanced technology products for the electronics, industrial, fabrics, and medical markets. Its corporate structure fosters innovation and has been a significant contributor to associate satisfaction. Employee turnover is a low 3 percent a year, and the company can choose new associates from the thousands of job applications it receives annually. In 2017, Gore was named one of the 12 legends on Fortune’s “100 Best Companies to Work For.” These companies have made Fortune’s list for all 20 years the magazine has published its annual “Best” rankings.

Critical Thinking QuestionsSources: “Our Story,” https://www.gore.com, accessed July 18, 2017; Jeremy Hobson, “What It’s Like to Lead a Non-Hierarchical Workplace,” http://www.wbur.org, accessed July 18, 2017; Alan Deutschman, “The Un-CEO,” Fast Company, https://www.fastcompany.com, accessed July 18, 2017; Claire Zillman, “Secrets from Best Companies All Stars,” Fortune, http://fortune.com, March 9, 2017; Daniel Roberts, “At W.L. Gore, 57 Years of Authentic Culture,” Fortune, http://fortune.com, March 5, 2015.